There is some debate as to what compelled Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, to take up the cause of the American Revolutionaries. Was it because the young man was disposed to hate the British for killing his father? Or was it because, at the dawn of the American Revolution, that Marquis had recently become a Freemason? Biographer Harlow Unger wrote in his biography of Lafayette, that when he first heard talk of the rebellion, it “fired his chivalric—and now Masonic—imagination with descriptions of Americans as ‘people fighting for liberty.'”

Whatever his motivation may have been, his journey to America catalyzed a long and active life that made him a legend in both countries. For his role in pursuing change for both France and the United States of America, he became known as “The Hero of the Two Worlds.”

Background and Early Life

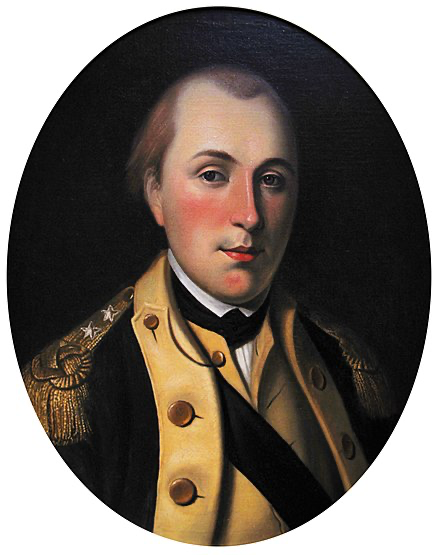

This famous Freemason’s full name was Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. He was born on September 6th, 1757, to one of France’s oldest families in the Auvergne. His ancestors served in the Crusades and alongside Joan of Arc. His was a family of nobles; his mother was Marie Louise Jolie de La Rivière, and his father, Michel Louis Christophe Roch Gilbert Paulette du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette, was a colonel of grenadiers.

Michel died when Gilbert was two, fighting a British-led coalition at the Battle of Minden in Westphalia during the Seven Years’ War. Lafayette became Marquis and Lord of Chavaniac, where he was raised by his paternal grandmother, Mme de Chavaniac. The boy moved to Paris in 1768 and was sent to school at the Collège du Plessis, part of the University of Paris, where he was enrolled in a program to become a Musketeer.

After Lafayette’s mother died on April 3rd, 1770, he inherited one of his nation’s most enormous fortunes. The following year, Lafayette was commissioned an officer in the Musketeers, with the rank of sous-lieutenant. While his duties were largely ceremonial, the young man longed for military glory and earned a captain’s commission in the French army, where he was appointed to the Black Musketeers in 1773. In 1774, the Marquis fell in love with and married Adrienne de Noialles, a woman whose family was even more prominent than the Lafayettes. They had four children and were happily married until she died in 1807.

After he lost his commission in 1775 from funding cuts to the military, Lafayette found himself in the city of Metz, attending a dinner with the Duke of Gloucester, the younger brother of British King George III. Lafayette’s heart burned this evening as he heard The Duke fretting about the American colonists taking arms against British rule. While the aristocrat mocked the revolutionaries and the Continental Army, Lafayette saw his fate unfold before him, saying, “My heart was enlisted, and I thought only of joining my colors to those of the revolutionaries.”

As for his Masonic membership, Lafayette said that he was raised in France before coming to America. He was made a Mason in either Loge La Candeur in Paris, or Loge Contrat Social of Paris. After coming to America it was also said that he was raised at a military lodge in Morristown, N.J., or at Valley Forge in 1777.

He also became a Royal Arch Mason, joining Jerusalem Chapter No. 8 in New York City on September 12, 1824. He then joined the Knights Templar in Morton Commandery No. 4 and in Columbian Commandery No. 1, both of New York City. In the Scottish Rite, he received the degrees in the Cerneau Supreme Council of NY, and was made a 33rd degree Mason and Honorary Grand Commander of that body.

Major General Marquis de Lafayette

In 1776, Louis XVI negotiated with American agents, thinking that supplying the Americans with arms and officers could restore French influence in North America. After catching word that French officers were being sent to America, Lafayette sought to join them and was enlisted as a major general despite being just 19. When the British caught wind of the negotiations, they threatened war against France.

The nation put its support for the revolutionaries on hold, but the young Marquis remained determined to go. His father-in-law, de Noailles, adamantly opposed his desire to fight for the revolutionaries, but Lafayette desired to go all the same. He purchased a ship, Victoire, for 112,000 pounds yet nearly backed out of his scheme after facing pressure from his wife and family. After some hesitance, the Marquis loaded Victoire with 5,000 rifles and ammunition and began his two-month journey to America on April 26th, 1777.

He landed on North Island near Georgetown, South Carolina, on June 13th and soon ventured to Philadelphia. While the Second Continental Congress was inundated with French officers who could not speak English and lacked military experience, Lafayette used his status as a Freemason to build relationships with key figures. Notably, Brother Benjamin Franklin, the new American envoy to France, wrote a letter to Congress urging them to accommodate the Marquis.

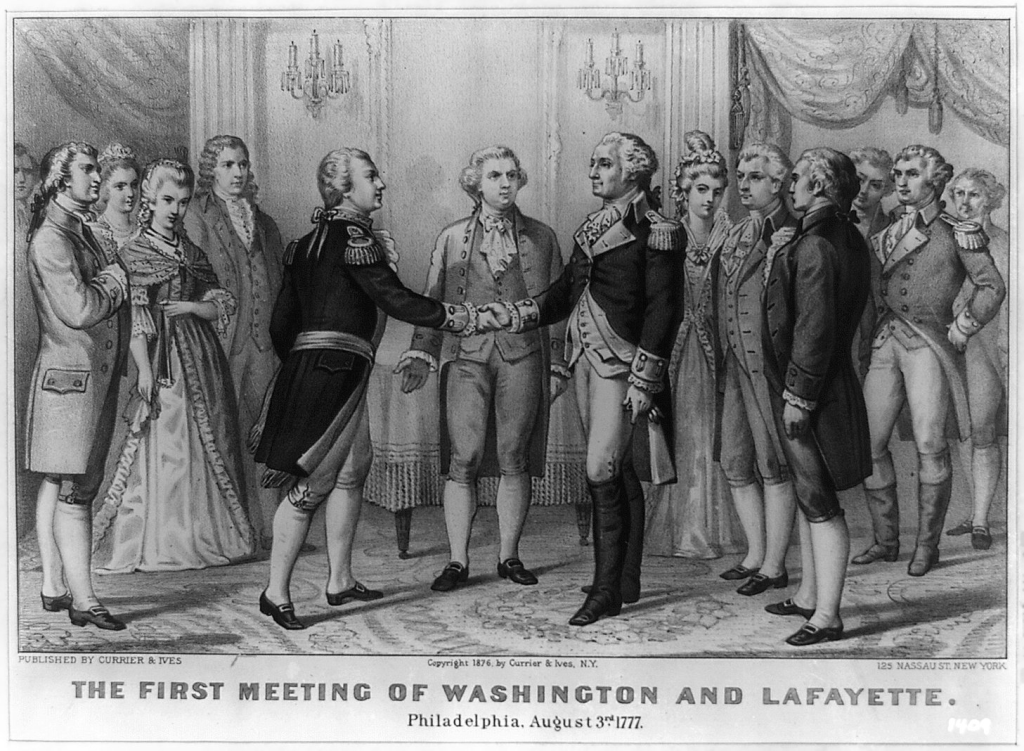

As he quickly became fluent in English, Lafayette offered to serve in the Continental Army without pay and was commissioned by Congress as a major general on July 31st, 1777. Within days, the Marquis met General George Washington, commander in chief of the Continental Army, and the two formed an instant bond, quite likely nurtured by their shared connection as Freemasons.

The American Revolution

The commanding general made the Marquis a member of his staff on which he served for six weeks. He got his first taste of combat at the Battle of the Brandywine, near Philadelphia, on September 11th, 1777. Lafayette was shot in the leg but rallied the American troops for a more orderly pullback before seeking treatment for his wound. Washington recognized and cited him for his valor, choosing to give the Marquis command of his own division.

His role in the revolution only grew from this moment on. He spent the legendary winter at Valley Forge camped with Washington, coming to respect his leadership more while the two grew closer. Lafayette played a critical role in the Battles of Barren Hill, Monmouth, and Rhode Island. Lafayette returned to France in June 1778 to broker more support for the United States. Working alongside Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, the three persuaded Louis XVI to provide additional troops and supplies to aid the colonists. Lafayette returned to America in April 1780, having secured 6,000 French infantry under the command of the Comte de Rochambeau and six ships of the line.

One of his most significant accomplishments of the war came in the summer of 1781 when Washington dispatched him to stop British raids along the James River in Virginia. He was given command of an army and began hit-and-run operations against forces under Benedict Arnold. Lafayette’s force chased British commander Lord Charles Cornwallis across Virginia, forcing him into a corner at Yorktown. French and American forces laid siege to Yorktown, forcing the surrender of the British and securing Lafayette’s status as the “Hero of Two Worlds.” For his part in the revolution, the Marquis became an honorary citizen of several states on a visit to the United States.

Return to France and Revolution

Lafayette returned home in early 1782 and received a hero’s welcome at the Palace of Versailles. He was promoted to maréchal de camp, was made a Knight of the Order of Saint Louis, and helped negotiate The Treaty of Paris between Great Britain and the United States in 1783.

Working with Thomas Jefferson, he established trade agreements between the U.S. and France to reduce America’s debt to its ally. The Marquis publicly advocated the end of the slave trade and equal rights for free black individuals and urged the emancipation of enslaved people in a 1783 letter to Washington, who was an enslaver. During a visit to Virginia in 1784, he addressed the Virginia House of Delegates and called for the “liberty of all mankind” while calling for an end to slavery.

Lafayette’s aristocratic position became more complicated as the French Revolution unfolded. He had close ties with Louis XVI and supported the idea of a constitutional monarchy. In the late 1780s, he worked with Jefferson to compose a draft of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which he presented to the revolutionary National Assembly. As the revolution raged on, Lafayette was still in service to Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette, whom he saved from a crowd that invaded Versailles on October 6th.

In December 1791, the Marquis spent a brief time as commander before the monarchy was overthrown in 1792 amidst a popular insurrection. Lafayette defected to Austria to avoid standing trial for treason but was captured and sent to Olmütz Prison until 1799 when General Napoleon Bonaparte brokered his release.

Though he escaped the Reign of Terror, Adrienne was arrested, and many members of her family were executed. Upon his return to France, Napoleon offered Lafayette membership in the new Légion d’Honneur, but he chose instead to retire from public life and became a farmer, even shirking offers from President Thomas Jefferson to become governor of the newly acquired Louisiana.

The Grand Tour

In 1824, Lafayette returned to the United States at the invitation of old friend President James Monroe. It was an emotional journey for Lafayette as he visited George Washington’s grave and was hosted at Monticello by the 81-year-old Jefferson. Crowds greeted him by the thousands in every city he passed through. On December 10th, 1824, the Marquis became the first foreign citizen to address the U.S. House of Representatives. What was meant to be a four-month tour across the original 13 states turned into a 16-month visit to 24, and included a two day visit to Cincinnati in May of 1825.

His popularity had not waned when he returned to France despite being years removed from politics. The short-lived July Revolution of 1830 gave Lafayette a chance to seize control of the government, but he declined. During the final years of his life, he served his nation by proposing liberal policies in the face of diminishing civil liberties driven by King Louis-Philippe. The Marquis de Lafayette caught pneumonia and died at age 76 on May 20th, 1834. He was buried next to his Adrienne at the Picpus Cemetery, per his wishes, under soil from Bunker Hill.

Upon his death, both Houses of Congress were draped in black bunting for 30 days at the request of President Jackson. Former President John Quincy Adams gave a three-hour eulogy of Lafayette. Today, towns and cities across the United States bear his name for his contributions to our nation.

Learn more about other historical Freemasons by reading our blogs on King David Kalākaua and Leroy Gordon Cooper!